With officially 49 ethnic groups and 160 ethnic sub-groups in Laos1, the question sounds like a provocation. For a small country about half the size of France and seven million and a half inhabitants, we are one of the most ethnically diverse country, grouped into four different language families: Tai-Kadai, Mon-Khmer, Hmong-Lu Mien and Sino-Tibetan.

Conveniently we cluster the ethnic groups souan phao (ສ່ວນເຜົ່າ sūaːn pʰāo) under three broad categories: the Lao Soung (ລາວສູງ láːo sŭːŋ), who live in the mountainous areas and account for 10% of the population; the Lao Theung (ລາວເທິງ láːo tʰə́ŋ), who live on the hillsides and represent about a quarter of the population; and the Lao Loum (ລາວລຸ່ມ láːo lūm) who reside in lowland areas and on the riverbanks of the Mekong. The Lao Loum, often referred as ethnic Lao represents about two-third population mostly from the Tai ethnic group, which I am part of. Thus, when trying to understand what Lao cuisine is about, I am only speaking from my experience as a ‘Lao Loum’, from the Tai ethnic group and unsure of my sub-ethnic belonging2.

The Tai ethnic group –not to confuse with Thai as in Thailand – is described by the Encyclopedia Britannica as: ‘Tai, also spelled Dai, peoples of mainland Southeast Asia, including the Thai, or Siamese (in central and southern Thailand), the Lao (in Laos and northern Thailand), the Shan (in northeast Myanmar [Burma]), the Lü (primarily in Yunnan province, China, but also in Myanmar, Laos, northern Thailand, and Vietnam), the Yunnan Tai (the major Tai group in Yunnan), and the tribal Tai (in northern Vietnam). All of these groups speak Tai languages’. Of these various groups, we share more than language roots: beliefs, clothing style, rituals, food too. In a not so unsurprisingly way, we have many common dishes and way of life. Look at the Isan people, 23 millions speakers of Lao - Tai language group who live in today’s Northern Thailand, the Khorat Plateau.

Historically, Laos spread wider than the current official boundaries extending to the Khorat Plateau as part of the former Lanexang Kingdom (15-18th century)3. We are ethnically, linguistically and culturally Lao. When the French arrived in Laos in 1893, the Kingdom was already pulled between the Kingdom of Siam and Vietnam. Although the French attempted to reconstitute Lao former territories, they conceded the Khorat Plateau to Siam in the Entente Cordiale of 1904. This cemented the split of the Lao-speaking world at the Mekong river with the left bank eventually becoming modern Laos and the right bank the Isan region of Thailand. Isan refers to the local development of the Lao language in Thailand. Besides of language, we share rituals, belief in Buddhism Hinayana, traditions, biodiversity and natural habitat. Crossing over to Nongkhai, Udonthani or wandering in the streets of Bangkok, we feel home. Our shared ethnicity and way of life explain if needed the likeness of Lao and Thai Isan cuisine, like siblings in the same family.

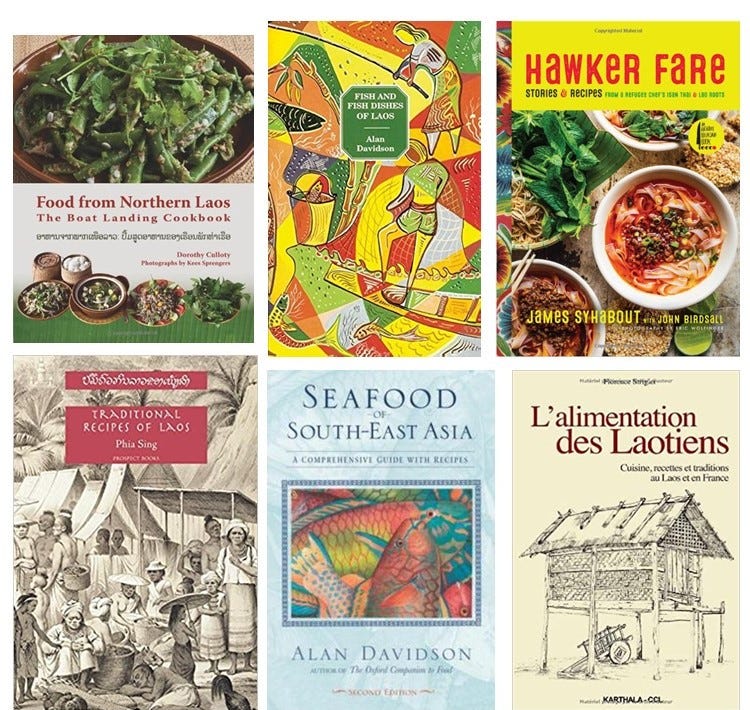

What characteristics has Lao cuisine? I looked at the internet, Lao cookbooks, Southeast Asian4 and Thai cookbooks5. The most interesting and hearty description is coming from by a nutritionist turned ethnologist, Florence Strigler in her French book “L’alimentation des Laotiens” (the food of Laotians)6.

Lao cuisine is rural

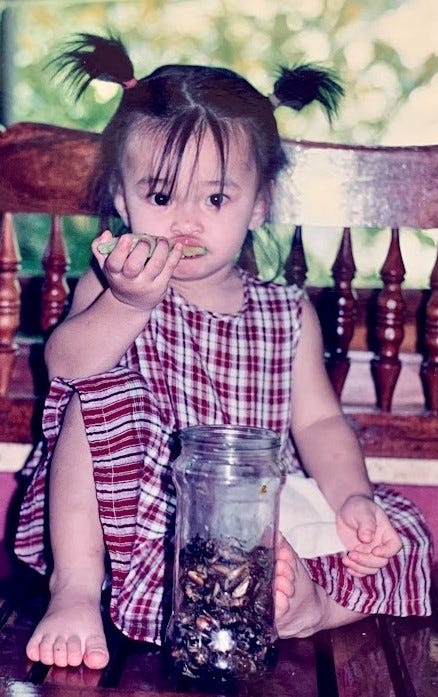

Lao has been a poor country, isolated from the global economy until early 2000. Natural forests covered 78% of its land area7 until 2010 and the country has been blessed with a rich biodiversity8. Most the villagers were harvesting from the forests and surrounding rivers or ponds. We forage roots, bamboo shoots, young leaves of mango trees, wild figs, galangal or ginger flowers, water hyacinth flowers, neem, piper betel leaves, khilek (kassod tree), pepperwood, mushrooms, fungus, river algae (ສາຫລ່າຍ sǎː lāːy), anything green that does not kill you.

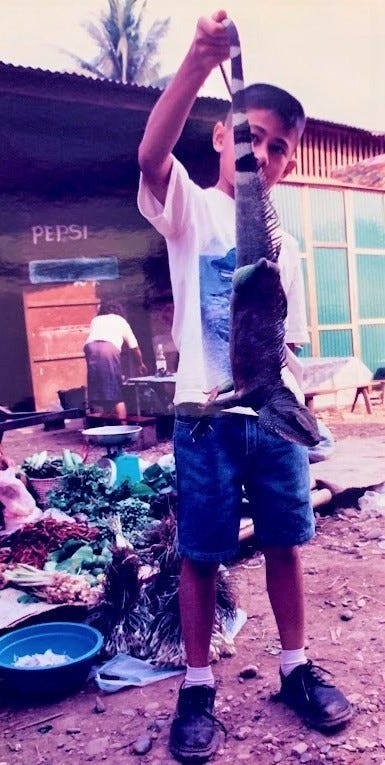

We also eat anything that flies or has four legs except tables (and dogs). At village KM52 from Vientiane, you can find deer meat, iguanas lizards at the local market. Insects are staple food from water beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, hannetons, red ants’ eggs, honeybee larvae, bamboo caterpillars, or silkworms. We also appreciate the mollusks, paddy crabs, snails or frogs. Buffalo skins (ຫນັງຄວາຽ năŋ kʰwáːy) or offals (ເຄື່ອງໃນ kʰɨ̄aŋ nái) are gourmet finds. This is not so much that we like exotic food, but Laos remained until recently a rural country with little agro-processing and junk food. Remote villagers put any protein they could on the phakhao ( low bamboo table).

Fishes and shellfish are a large part of our diet. Alan Davidson in his book on Fishes and Shellfish of Laos counted more than 250 species (1975) and Ian Baird further detailed these to be around 300 in 1999. Fishes are eaten raw, dried or smoked.

While neighboring countries eat white rice, and use glutinous rice for dessert or to transform into alcohol, Lao (Tai ethnic group) eat glutinous rice khao niaov (ເຂົ້າຫນຽວ kʰȁo nȋaːw), that is left to soak for a whole night to steam the next day. Glutinous rice represents 85% of the rice production in Laos. A proverb says that “a house where glutinous rice is eaten, is inhabited by Lao people”. Rice noodles have been introduced over time by the Chinese or the Vietnamese.

We barely cook our food. A lot is eaten raw9 and unprocessed. Meat or fish is minced and cooked with lemon juice in laab (ລາບ lȃːp) a cold salad of minced meat or fish with plenty of spices and herbs; or salted and left to dry like the beef jerky sin heng (ຊີ້ນແຫ້ງ sȋːn hɛ̏ːŋ) or dried fish (ປາແຫ້ງ paː hɛ̏ːŋ); or fermented like our national anchovy sauce padaek (ປາແດກ paː dɛ̏ːk) or fish roes (ສົ້ມໄຂ່ປາ sŏm kʰāy paː) or smoked like payang (ປາຢ້າງ paː yȃːŋ) to be able to keep for a longer period. Vegetables are also fermented ( ສົ້ມຜັກ sŏm pʰák) or blanched and gently mixed with padaek like in soup phak (ຊຸບຜັກ sūp pʰák); insects are grilled or toasted with salt eaten as a snack. The Lao cooking methods referenced by ethnologists and nutritionists are: grilling, smoking, steaming in leaves, fermenting, drying or boiling.

While the preparation time can be long with the mincing of herbs like the lemongrass, galangal, shallots, kaffir lime, meat or fish accompanied by a bountiful plate of vegetables (in laab for example), the mixing is quick, less than ten minutes overall. Vegetable salads made of papaya tam mak houng, long beans tam mak thoua, cucumber tam mak teng, green mangoes tam mak mouang are sliced and gently pounded with chilies, padaek, shrimp paste kapi, tamarind, sugar, tomatoes and small eggplants. At times, fermented salted paddy crabs are added. And let’s not forget our cheo, (ແຈ່ວ cɛ̄ːw) too many varieties to number, our sauce made of chilies and spices consisting of a base of grilled shallots, garlic and chilies pounded with tomatoes cheo mak leng, water beetles cheo mengda, mushrooms cheo hed, rattan shoots, dried fish or paddy crabs cheo nam pou.

This is where the earthy taste come from. What soil and freshwater fish and roots have in common is that they often contain geosmin, a protein produced by various bacteria and fungi. As well as the earthiness, it is rich in umami10. We have seven or more tastes to our cuisine: salty, sweet, sour, bitter, umami but also astringent, pungent. We are wild, vegetables like the S'dao are not bitter enough, we add bile to our laab or anchovy sauce to accompany grilled lemongrass beef.

Lao food is viscerally rural and stubbornly earthy.

Lao cuisine does not know the deep frying or sautéing techniques. It stews only to get the buffalo skin tender. Inside the Southeast Asian Kitchen, a publication of the ASEAN secretariat, lists squarely that most of Lao food is boiled, grilled or steamed while Thailand adds frying, roasting, and Vietnam outbids with braising, stir-frying, pan-frying, deep-frying.

Thus, when reading Lao cookbooks, it is easy to spot dishes that have been imported over time from other countries such as the sautéed veggies, the noodle soups, a Chinese heritage, the ragout or paté chaud from France or the deep-fried spring rolls cha gio or pancakes ban xeo from Vietnam. When chefs swoon over spring rolls or advise to sauté or boil the meat for laab, you know that’s a kind of compromission.

Lao Cookbooks with an earthy taste

We refer this type of Lao cuisine to aharn pheun meuang (ອາຫານ aː hăːn ພື້ນເມືອງ pʰɨ̂ːnmɨ́aŋ)11 or 'food from the village / city' or aharn ban hao (ອາຫານບ້ານເຮົາ aː hăːn bȃːn háo) ‘food from our home’. With rapid urbanization, integration of Laos in regional and global economies, mass tourism, this way of life and cuisine is disappearing at the inexorable pace of deforestation12. This is further accelerated by the contribution of overseas influencers taking over Instagram or YouTube sharing their own experience of what Lao food is about. Sometimes, it gets really weird, hydroponic13.

From this viewpoint of Lao food as being rural and raw, here are some cookbooks you might want to have in your kitchen. The work of Alan Davidson on Fish and Fish dishes of Laos is inescapable14, he is a ‘savant’ and has lived in Laos as UK Ambassador. He helped reprint the book of Phia Sing, the chef of the Lao Royal Palace. The Boat Landing Cookbook is a must-have too, it reflects the food of northern of Laos, very much alike the food I have experienced in the rural villages of Houaphanh province. You can download the ebook from its website15. Let's also mention the ok work produced by Friends International, with a mix of great and not-so-great recipes laid out in a funky design. And finally, a warm recommendation for Hawker Fare by James Syhabout, an Isan16 American Chef, Proprietor of Commis, a Michelin-starred restaurant in Oakland offering French American food. His incursion into Lao cuisine has given one of the best Lao cookbooks so far.

Davidson, A. (2004). Seafood of South-East Asia: A Comprehensive Guide with Recipes [A Cookbook] (2nd ed.). Ten Speed Press. And its companion: Davidson, A. (2003). Fish and Fish Dishes of Laos. Prospect.

Sing, P. (2013). Traditional Recipes of Laos. Prospect Books (UK).

Culloty, D. (2010). Food from Northern Laos: The Boat Landing Cookbook. Galangal Press.

Auer, G. (2011). From Honeybees to Pepperwood: Creative Lao Cooking with Friends = Nap Ta Mang Phang Chon Thng Sakhaan. Friends International.

Syhabout, J., & Birdsall, J. (2018). Hawker Fare: Stories & Recipes from a Refugee Chef’s Isan Thai & Lao Roots. Anthony Bourdain/Ecco.

From these books and my travels up north and down south of Laos, the perfect Lao meal is still the simple grilled lemongrass chicken or fish, dried and grilled meat Savannakhet style, a papaya salad with salted paddy crabs, glutinous rice, a cheo sauce, any of them. Something you can pack on the go to the rice field or the Library of Congres.

Happy cooking to all.

https://minorityrights.org/country/laos/ - The actual number of ethnic groups is thought to be much higher, as high as 237 according to one United Nations Development Program (UNDP). https://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Laos/sub5_3c/entry-2962.html

The Lao-Tai Family includes eight ethnic groups: Lao, Phouthai, Tai, Lue, Gnouane, Young, Saek and Thai Neua.

Stuart-Fox, M. (1995). The French in Laos, 1887-1945. Modern Asian Studies, 29(1), 111–139. http://www.jstor.org/stable/312913

Tan, C., & Oshima, N. M. (2007). Inside the Southeast Asian Kitchen. ArtPostAsia. Other books consulted: - Ho, A. Y. (1995). At the South-East Asian Table. Oxford University Press, USA; Coll. (1999) Specialités de l'Asie du Sud-Est. Singapour, Malaisie, Indonesie : Un voyage culinaire. Konemann-Ellipsis, Culinaria.

Too many to list them but I like the cooking of Vat Bhumihit, Andy Ricker (Pok Pok, The Drinking Food of Thailand, Pok Pok Noodles), the encyclopedia by Phaidon, David Thompson and the many Thai language cookbooks.

Strigler, F. (2011). L’alimentation des Laotiens: cuisine, recettes et traditions au Laos et en France. KARTHALA Editions.

https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/LAO/ - Alas, but from 2000 to 2020, Laos experienced a net change of -1.47Mha (-7.2%) in tree cover.

Lao biodiversity can be explored in this digital database: https://www.phakhaolao.la/en

Raw food: unprocessed, unrefined that is eaten raw or cooked under 42 degrees celsius (about 108 F)

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/wordofmouth/2014/jul/29/why-some-people-love-earthy-flavours

local; indigenous/native; people's, national

It is noted though that Isan food is vibrant while Thailand has urbanized faster than Laos. So there might be some hope here.

Imagery - growing without soil.

Ian Baird, historian and geographer listed more than 300 species in his work “The Fishes of Southern Laos” published in 1999. He declared that “Apart from the Amazon River basin in South America, and possibly the Congo River basin in Africa, the Mekong River basin is the richest in the World in terms of freshwater fish biodiversity”. Check this out: https://www.academia.edu/1046731/The_Fishes_of_Southern_Lao

Many thanks to the generous author : https://foodfromnorthernlaos.com/

Born in Ubon, across the Mekong river, just 200 km from Paksé, the capital of Champassak province. Lao and Thai have been trading for centuries between the two cities.