They sit in day-long community events without complaining. They help with carrying the food to the pagoda, they clear the tables and the dishes too. They talk to the loud in-laws and chat about the nothings of life. They have learned a few Lao words or excelled at it. They love their spouse ຮັກເມັຽ hāk míaː and obey their whims ເຮັດນຳເມັຽ hēt nám míaː literally ‘act according to the spouse’. They are always willing to give a hand and bend to silly ways of doing things. They are not flamboyant nor arrogant, they blend with the group, well-educated and non-judgmental. They are stoics. No farang can imagine these expectations unless they have courted the Lao lady ຜູ້ສາວລາວ pʰȕː săːo láːo (phousao lao) for a couple of years.

Farang is a common and neutral word used in Laos and refers initially to the French people who influenced and ruled the country for almost a century. According to popular belief, it is an onomatopoeia formed from the sound associated with ‘France’ ຝຣັ່ງ frāŋ or its adjective ‘français’ ຝຣັ່ງເສດ frāŋ sȅːt. The word englobes nowadays all foreigners with white skin color. It is also used in Thailand and Cambodia (‘barang’) although explanations about the source of the word varies1.

The farang sons-in-law realize only too late they are marrying a community and they can choose to be part or ignore it. Then, one can wonder at what cost. The World Happiness Study conducted by data analytics firm Gallup2, insists that being part of a community is among the five pillars of well-being. In their statistics, six of the top twelve countries where people are most satisfied with opportunities to meet people and make friends are in Southeast Asia. The region is an outlier on this question for cultural reasons: “Asians are more collectivistic. They put group and community desires over their own. Southeast Asians place importance on neighbors, friends, families and communities (…) social wellbeing is woven into the cultural fabric of Southeast Asia3”. Why is there such a high expectation from sons-in-law but little expectations from daughters-in law?

Matrilinear traditions

Lao people from the Tai ethnic group to which I belong4 have a matrilineal tradition5 whereby sons-in-law are expected to move in the home of the bride’s parents and inheritance goes to the daughters rather than the sons. The younger daughter is expected to take care of the aging parents and will inherit the family house6. The newlyweds live under the same roof until they have a child and leave to establish a different household. Sons-in-law are expected to obey the house’s rules and to hold into high respect their parents-in-law7.

If the farang sons-in-law are of higher social status, meaning they are wealthier, have better education and social capital than the bride, they are highly considered as they will lift the family’s prestige ກຽດ kȉaːt - a noun defined as honor, renown, dignity, fame, prestige, reputation, glory. If they are of the same status, their position will remain unchanged and if of lower status, it is trusted that their daughters have chosen someone with a good heart or a high potential.

Professor Amphay Doré uses the concept of ປຽບ pȉap - a noun meaning high position; good reputation - in explaining these social dynamics but this word is mostly used in context of conflict ເສັຽປຽບ sĭaː pȉaːp (lose out; be at a disadvantage; lose by comparison); ເອົາປຽບ ao pȉaːp (take advantage of, gain the advantage, acquire honor); ໄດ້ປຽບ dȃy pȉaːp (get an advantage; get the upper hand; win out). From a common perspective, I think ກຽດ kȉaːt is more appropriate than ປຽບ pȉap.

Daughters-in-law

On the contrary, sons are to follow their spouse and serve his in-laws. It is a loss for the family and not much is expected from the departing sons. As it is the informal rule, they shall love their wife ຮັກເມັຽ hāk míaː and follow them ເຮັດນຳເມັຽ hēt nám míaː whether the latter are Lao or farang. A ເມັຽຝຣັ່ງ mia farang is not expected to make efforts to join the Lao community, rather, our sons will join hers. Lao parents are invited to western functions, modern life events and blend in as they become more at ease in the host country or a globalized world.

It is a bonus if the daughters-in-law remain close and serve their husbands’ families. They are then held in high esteem in particular if they are farang. They are adored and are spoken at length about their good behavior, their generosity. My great aunt, tata Françoise Souvannavong was one of them. She married my great uncle phagna Oukeo Souvannavong, the very first Lao graduate in engineering from the School of Ponts et Chaussées (Paris) and director of planning in the Lao Government who oversaw the Nam Ngum river dam, first in the country (1968) located at Tha Ngone in Vientiane Municipality.

She folded herself to be a loving companion, raising their children with French and Lao traditions. Her daughter Jacqueline, Kikou, remained close to the Souvannavong family in France and inherited the curse of being a straight talker. Tata Françoise wore Lao outfits with elegance, went to the Lao temples, spoke Lao and was fond of the younger generation. She officiated at the baci ceremony of our daughter back in 1997, when she was still in good health. After my uncle’s passing (1914-1998), she retired in France to stay with Kikou and wrote a cookbook “Culinary Traditions of Laos”8, a testimonial of her affection for Laos.

Ways to be a farang son-in-law.

Mixed marriage is not unfamiliar to the Lao people. Unions and companionships happened early in the Protectorate. Prince Souvanna Phouma, then prime minister married in 1933 Claire Aline Allard9, daughter of Numa Prosper Allard, a French civil servant who served as the president of Laos' chamber of commerce and agriculture. Her mother was Lao.

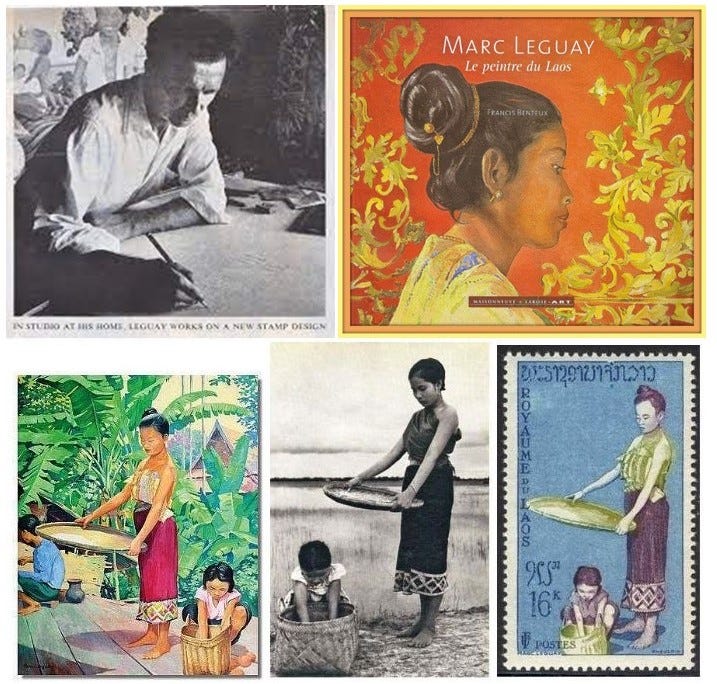

Tiao Sisouk Na Champassak wed his first wife Christiane Guida10 in 1930. In our family, we celebrate the Drouot who twinned their destiny to the Souvannavong family when George Louis Drouot, Commissioner of the Republic in the province of Khammouane, married Gna Mae Thet, daughter of Thit Som Luang Souvannavong, at the beginning of the 20th century. Of their descendants, Michel Drouot (a.k.a Somsanouk Mixay) is probably the most prominent as he stayed with the new regime and founded the English-Lao newspaper Vientiane Times. A beloved promoter of Lao culture and arts, he recently passed away, sending emotional tremors throughout the world among the extended family and friends11.

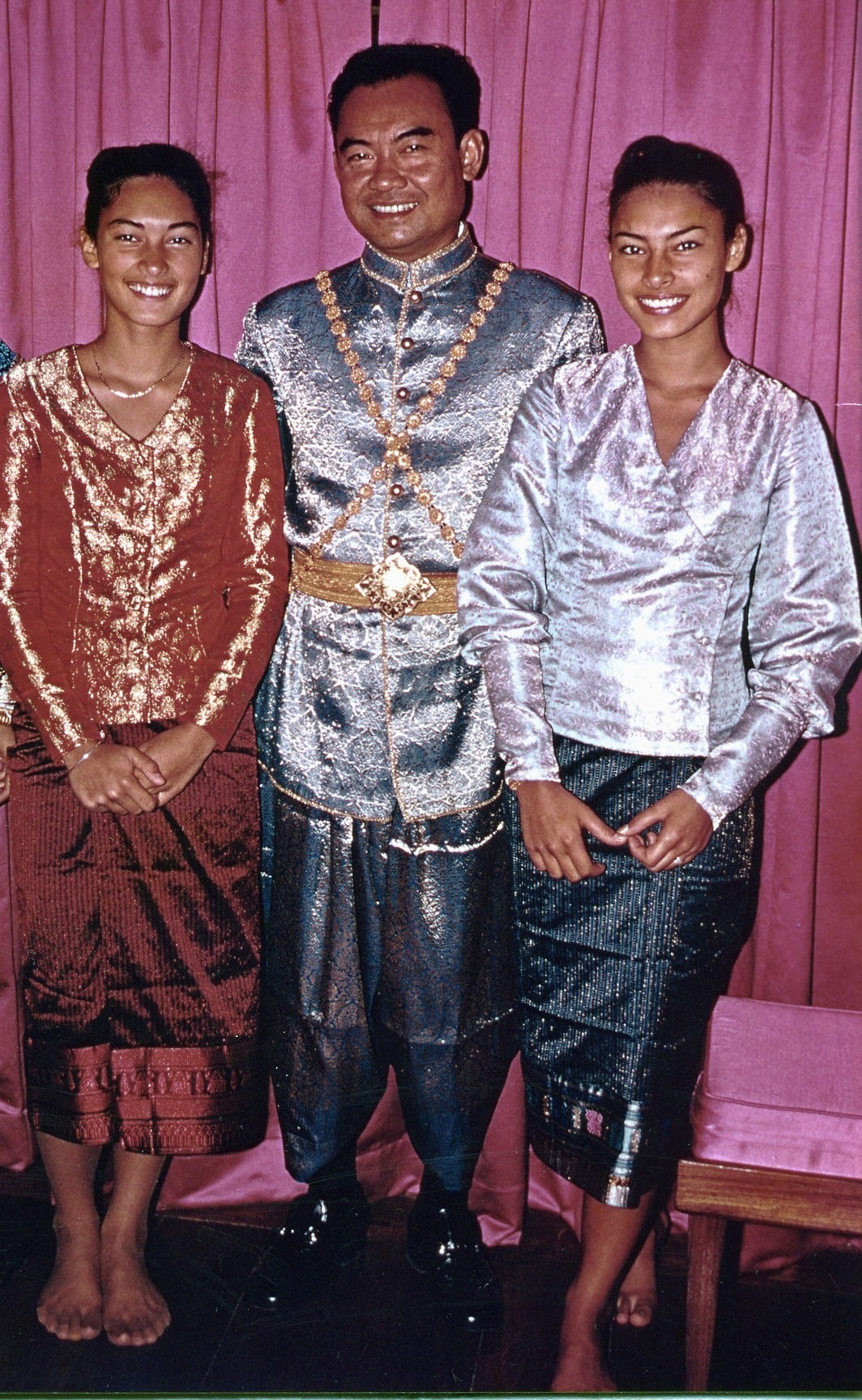

In those times, marrying a farang was a mark of modernism and a testimonial of our ability to evolve in an international arena. Their children were good-looking, tall, with wide-eyes, well-educated and at ease both in Lao and French society. Just look at Soraya, Nanda and Vorana Na Champassak exemplifying a certain canon of beauty in the eyes of Lao people. Sons and daughters of high-ranking officials were sent to Paris, Toulouse or Lyons to further their studies, and came back with French fiancés.

But being an ideal in-law is above all a way of being and behaving in Lao society. Take Alain, my brother-in-law. In his 30-year marriage with my sister, I think I have seen him only twice flew off the handle. From the outset, he joined community events, carrying picnic bags, manning the BBQ station, sitting at the back of the pagoda’ sim, the prayer hall. Sometimes he will take a book and quietly wait in a corner. Most of time, he would engage in about-nothing conversations with the elders, enjoying a beer or a glass of wine with my loud father and his friends.

And there is also Marc Mouscadet who married Orathay ‘Ching’ Nhouyvanisvong. He tells me “I have always liked being with the Lao people. I liked their lightness, their easy-going attitude, dancing and singing all night long. When I dated Ching, we organized luncheons with family members, we never part our ways. When we were stationed in Bangkok, we saw everyone, family, friends passing by. There were mornings we had to remember, so who is here today?”. Marc was a director at Indosuez Bank and their apartment overlooking the Chao Praya river had a superb view of the city. The couple has been fondly talked about for their ability to stay simple and welcome any Lao of the street in their posh house.

Marc’s true interest in the Lao people translated by his teaching at the Lao Faculty of Law, his commitment as administrator of the Lao Cooperation Committee (Comité de Coopération du Laos); his researching and publishing about Lao history12; his engagement with the intellectual and diplomatic circles. More importantly maybe is that he and Ching continue to organize family and Lao community gatherings. He notes that it is more difficult to get the new generation to join these events: “I understand that they don’t want to spend their afternoon dancing the Madison” he joked. There are others like Marc who devoted themselves in their later years to researching into Lao culture such as Frederic Benson13, who worked for the International Voluntary Services, Inc. (IVS) (1968-1970), married a royal, and donated their pictures of Laos to research centers such as the one from the University of Madison Wisconsin. This Lao life developed as they thrived in their own expatriate and French societies.

What happens to the not-so-ideal farang sons-in-law? Are we two worlds that juxtapose rather than intersects at two points, where a space is created to thrive together? How to be together and still retain our uniqueness? More generally, this raises the question of what it means to be Lao when Lao-ness become more farang, with our transnational children – of mixed marriage or not - who are born in or decide to settle in France, Australia or elsewhere. How does one both embrace globalization and maintain one’s culture? How do we reinvent our relations with a country we left but who holds the roots – and controversially, maybe the future - of who we are?

Pattana Kitiarsa explains that this “was borrowed from Muslim Persian and Indian traders during the Ayutthaya period, when it was used to refer to the Portuguese, who were the first Europeans to visit Siam in significant numbers” in ‘An ambiguous intimacy: Farang as Siamese Occidentalism”, The Ambiguous Allure of the West: Traces of Colonial in Thailand (Hong Kong, 2010: online edn, Hong Kong Scholarship Online, 14 Sept. 2011).

Gallup has also been conducting studies on well-being for 80 years and has expanded to 155 countries – Latest thinking can be found in : Clifton J. (2022). Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It. Gallup Press.

Quote by Gallup’s Director for Asia-Pacific, Chayanun Saransomrurtai. See page 144 of Blind Spot

Laos recognizes about 50 ethnic groups and 200 ethnic sub-groups from four ethno-linguistics groups: Lao-Tai (62.4 percent), Mon-Khmer (23.7 percent), Hmong-Iu Mien (9.7 percent), and Chine-Tibetan (2.9 percent). See: https://laos.opendevelopmentmekong.net/topics/ethnic-minorities-and-indigenous-people/

Studies have shown that since the New Economic Mechanism (NEM) policy in 1986 and globalization, there has been a gradual erosion of the matrilineal Lao Lum tradition with important consequences for gender equality in the country: Schenk-Sandbergen, L. The Lao Matri-System, Empowerment, and Globalisation. The Journal of Lao Studies, Volume 3, Issue 1, pps 65-90. ISSN : 2159-2152. https://www.laostudies.org/system/files/subscription/JLS-v3-i1-Oct2012-schenk-sandbergen.pdf

The State Inheritance Law now distributes assets equally among siblings. Shenk-Sandbergen explains in the same study how a well-intentioned law disrupts matrilinear traditions and might undermine and erode the traditional value placed on the act of caring for the aging parents.

Dwelve into a fascinating description (in French) provided in Amphay Doré, « Le gendre lao. Essai d’anthropologie du pouvoir féminin dans la société traditionnelle de Louang‑Phrabang », Moussons, 1 | 2000, 21-40. https://doi.org/10.4000/moussons.8833. Check also the article from Formoso Bernard. Alliance et séniorité Le cas des Lao du nord-est de la Thaïlande. In: L'Homme, 1990, tome 30 n°115. pp. 71-97; doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/hom.1990.369282

Oukeo Souvannavong, F., Traditions culinaires du Laos, Editions Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris, 2002.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aline_Claire_Allard

The genealogy tree of the royal family of Na Champassak can be found here: https://www.royalark.net/Laos/champasa.htm

https://laotiantimes.com/2023/01/25/publishing-pioneer-somsanouk-mixay-dies-at-84/

https://marcmouscadet.academia.edu/research

https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AFredericBensonImages