[Warning: this blog discusses impermanence of life. Content can be distressing]

“C. just passed away. Do you have the death certificates of your children? We are unable to proceed with the execution of her will until these documents have been provided”. How? How can we get certificates when we don’t even know where the mass grave is located. This was 49 years ago. I check with R. He also returned to the area to look for the site, at the back of a nothing hospital. He was 12 or 13 years old, not a child anymore and not a man yet, so he was spared but tasked with carrying the corpses to the graveyard. He told me, it is somewhere near Battambang, two three kilometers before. The mass grave also hosted their grandmother and Aunt R. The other family members, Aunt H, her husband, uncle H., grandfather were in different mass graves. We took the old train with S., their elder brother, between Phnom Penh and Battambang.

The officials were unwilling to help. I finally convinced a head monk of a nearby pagoda to write something on a loose paper. I don’t know if the French notary will ever accept this. Years back, we brought a handful of earth from the native village of T. to put in the family stupa at Wat L. in Phnom Penh. Because we didn’t have any remains of the lost ones. We needed a place to honor their memory, a place to worship on holy days.

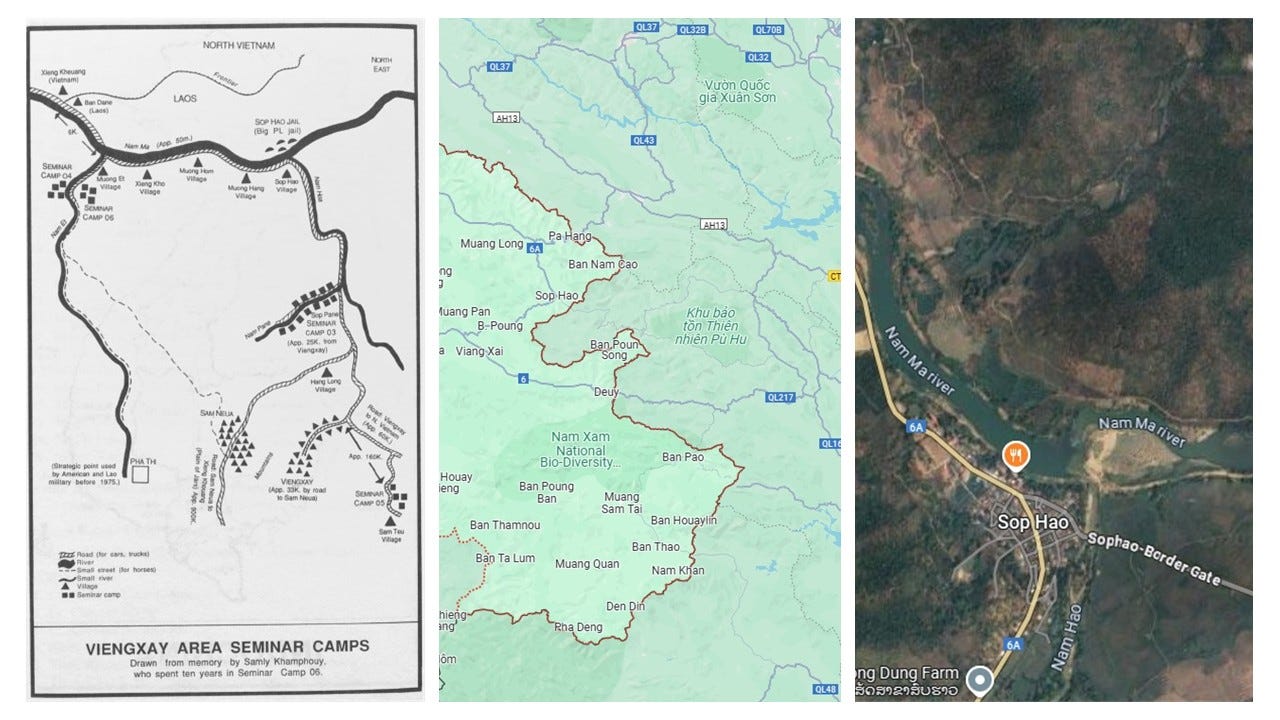

“Do you have the article that says where grandfather died, and the list of the people who were with him?” – Was it the article in the New York Times? “No, the list of the people sent to the reeducation camp with him”. I realize I did not print the testimonial from Colonel Khamphan Thammakhanti of the Royal Lao Armed Forces. H.R.H. Tiao Prince Mangkra Souvanna Phouma1 shared excerpts of his diary and made the information available on his website Lao Committee for the Defense of Human Rights. He listed the people sent to the reeducation camp and described with details the gulag life2.

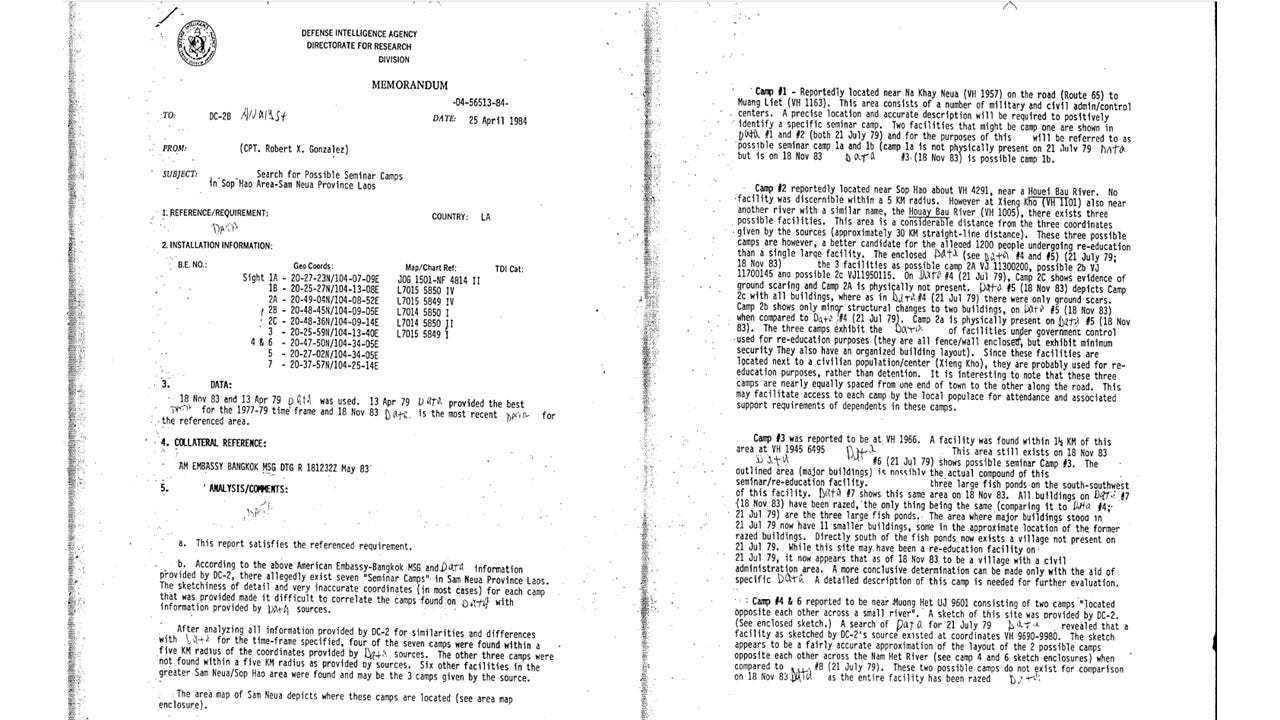

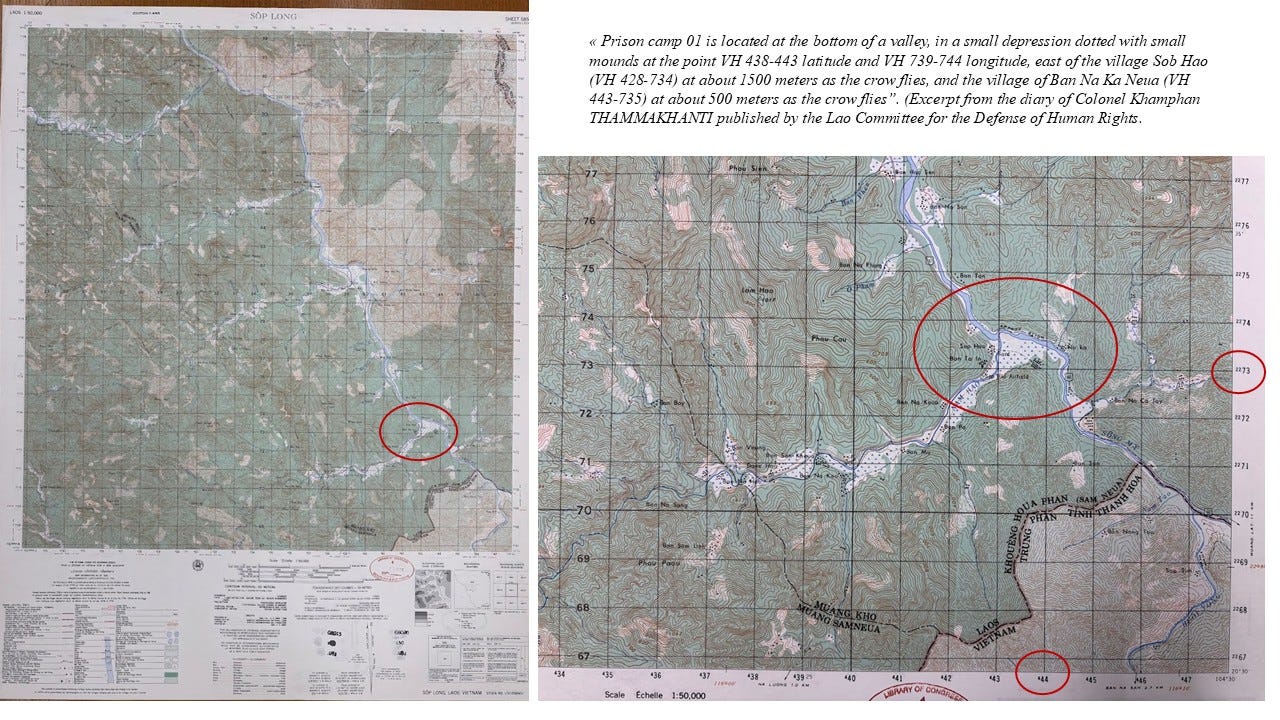

The diary describes: “It is Camp 01, in Sob-Hao, Houaphanh. The coordinates were 438-745. He arrrived on November 15, 1977 at 9 p.m. with a group of 11 prisoners from Muong Lièt, their previous place of detention. They are: 1. H.R.H.Prince Souphantharangsi ; 2. H.R.H. Prince Bovone; 3. H.R.H. le Prince Thongsouk; 4. HRH Prince Sisavang; 5. H.R.H. Prince Manivong Khammao; H.E Tiao Souk Bouavong; H.E. Bong Souvannavong; Police General Lith Lu Nammachak; M. Phommy Phanvong; M. Thong; M; Phimpha. The King, the Queen and Crown Prince Savang arrived on November 24, 1977 around 22 pm”. There are reports from the CIA corroboting the information including one dated 1984 listing all the potential reeducation camps throughout the north of Laos.3

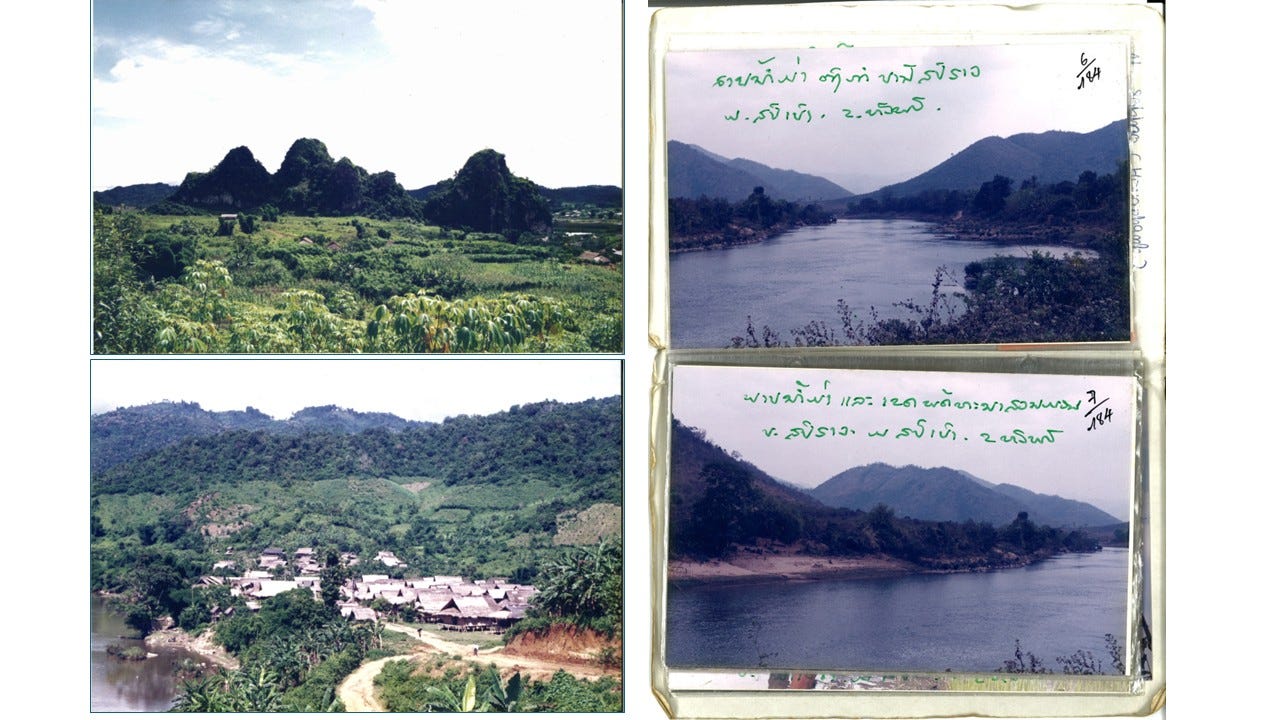

We traveled to Houaphanh province in 1999 with our daughter B. driven by our research on Lao textiles. The Tai Deng ethnic group was well known for the intricate silk weaving and the significance of the motifs and patterns. We went to Sob-Hao. It was still a village without running water or electricity, no paved streets. A water pump served the village.

We decided to bathe in the Nam Ma River. I was oblivious that my grandfather died only 1500 meter away, by the crow flight. As we left Sob-Hao to travel to Sam Tai, my husband pointed at the school: this is where the political meetings took place. What the heck didn’t he tell me?

At that period, I met Thou Loung Phan, a prominent member of the Royal family. He was a man of character, strongly built, speaking loudly and warmly. For being the granddaughter of Bong Souvannavong, he bestowed me with his affection and trust. Out of nowhere, he promised that we will go back there to find his bones. We both knew this wouldn’t be allowed. He passed away before we could go. I google where Sob-Hao is and visit the Library of Congress to find the maps. Where is 438-745?

“Tata N. has convinced all the sisters that we should disperse the ashes of your grandmother. Because we are all too old, half of us are living in France and there will be nobody to take care of the ashes at the pagoda after we are gone. Nobody will come to put the flowers, burn the incense sticks or clean the photos on the holy days. I disagreed but all the sisters said we should. So, we dispersed the ashes on the Mekong river”. This was Saturday May 31, 2025 in Vientiane.

I am perplexed. We keep doing these soukhouan “call for the souls” ceremonies to gather the 32 souls supposed to live in our body and here we are dispersing the ashes. Zillions of particles of soul going everywhere, that does not make any sense. I ask A.I. to explain the contradictions. Ah… the concept of 32 souls is only valid when we are alive. After that, it’s about impermanence and nothing really matters so we can just disperse on the Mekong as the Hindi do on the Ganges river to help the deceased reach Nirvana. I check the writings of Marcel Zago, Charles Archaimbault and Nhouy Abhay “Death and Funeral Rites”4 that dates back from 1956. He narrates “Very early, before the sun has even risen, parents, friends, monks, and the entire village walk to the extinguished hearth and gather what the flames have left of the departed: a handful of ashes, enough to fill a small jar. This jar will be placed in the pagoda, awaiting the final ceremony when it will be carried to the stupa— raised to honor, with dignity, the memory of the virtuous man, whose fleeting risks now seem so slight”. It seems unusual to scatter the ashes. I found it more romantic when the ashes of my paternal grandparents were buried at the foundation of the great temple of Paksé in Champassak, as they were among the founders of the site.

What is life and death? When our soul wander, we call the monks; they come with a white cloth and cover our whole body. They chant and spit holy water. The bad spirits are out of our body, so they said. And we go on until it is too painful to carry on. On one side, the living who ignore their trauma; on the other, thousands of tourists who pass by.

On July 12, 2025, UNESCO officially inscribed Choeung Ek Genocidal Center—along with the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and the former M-13 prison—onto the World Heritage List. Choeung Ek is this place where there is a memorial stupa with glass sides that reveals about 5000 skulls and bones of victims that are stacked on multiple tiers. There are about 800 visitors per day during high season so an estimated of 300,000 tourists per year. Are my siblings, my grandfather, my grandmother, my aunts and uncles stuck in there?

We, humans, are so flawed. We look for bones, we disperse the ashes, we stack up the skulls, we ignore what haunts us and we ask our children to carry on the weight of the past. We are not heroes. We don’t need heroes. We just need a 9-to-5 job, put dinner on the table and watch Netflix.

Prince Mangkra Souvanna Phouma ສຸວັນນະພູມາ (24 February 1938 – 8 January 2025) was a royal in the Kingdom of Laos and the son of Prince Souvanna Phouma, (7 October 1901 – 10 January 1984), the leader of the neutralist faction and Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Laos several times (1951–1954, 1956–1958, 1960, and 1962–1975). In Paris, Prince Mangkra led the resistance in exile and created the Lao Committee for the Defense of Human Rights.

Lao Committee for the Defense of Human Rights: Diary of Colonel Khamphan THAMMAKHANTI of the Royal Lao Armed Forces, who was deported in 1977 and spent more than thirteen years in one of the six "re-education" camps known in the Lao People's Democratic Republic. http://www.laosnet.org/humanrights/camp01.htm

(1985) Camp I Houaphan Province/ Search For Possible Seminar Camps In Sop Hao Area Sam Neua Province Laos. https://www.loc.gov/item/powmia/pwmaster_140997/

The experiences of nine Lao refugees who escaped reeducation camps are vividly documented in 1985 interviews conducted by Joanna Scott at the Philippine Refugee Processing Center as they awaited resettlement in the US. The map in the picture comes from her book.

Scott, J. C. (1989). Indochina's refugees: Oral histories from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. McFarland & Co

Abhay, T. N. (1956). Rites de la mort et des funérailles. Revue France-Asie, 118-119, March-April.