Sadness comes through many ways, including an Instagram feed. I have never dined at Doikanoi restaurant, nor did I ever met Noi, the chef and owner of the first Lao restaurant shortlisted among Asia's 50 Best Restaurants.

Some years ago, images of her cooking joined my Insta feed. I casually looked at the photos, her cooking and dishes featured. I liked her no frills approach, her humility, and how familiar her food was to me. When her husband Mick started to post reels of their travels in the north of Laos, her cooking demonstrations, I liked her warm laugh, her benign approach to becoming an influencer. She was a Lao woman, as I knew them, simple, straightforward, welcoming, sharing without calculations. I spared a few exchanges1 with Mick during these years, but it was never about chef Noi, she is of the people you can only fall in love with.

The cooking of Chef Noi is what I call ອາຫານ ພຶ້ນເມືອງ2 aː hăːn pʰɨ̑ːn mɨ́aːŋ or ອາຫານ ພຶ້ນບ້ານ aː hăːn pʰɨ̑ːn bȃːn, food from the village. She cooked what I cooked when living in Vientiane, what I saw in the fresh markets of Xieng Khouang, Pakse or Houaphanh. She comprehended the essence of Lao cuisine: rural, earthy, bitter, sour, raw, utilizing the abundance provided by nature such as foraged vegetables, insects and game meat. It was the kind of food that Lao families prepare for you as you show up unannounced or for a celebration. She was offering everyday’s Lao family meal. I discovered new ingredients and new ways of cooking as she wandered in Luang Namtha or in the Akha, Tai Dam or Hmong ethnic villages where she found foraged vegetables such as ferns, mouse ear mushrooms. Mick documented their travels on Instagram. She offered afterwards what she has learned on the menu of their restaurant3.

Her cooking was authentic, uncompromising. She did not shy away from padaek (anchovy sauce) and would never tolerate a watered down recipe. She offered a steep learning curve to those unfamiliar with Lao food: Kaeng Khi Lek (cassia leaves curry) that I hated as a child refugee, or termite ants eggs.

It seemed from Doikanoi Instagram feed that her restaurant was simple, they had just started to be noticed internationally with a shortlisting on Asia 50’s best restaurants. It is this no-frills approach that made me feel so close to Noi. Her focus on food, her simplicity is unmatched. She was not on a crusade for Lao food fame, she was cooking Lao food, and sharing it. Speaking always in Lao in her videos, she never branded herself as “Chef Noi” and the name of her restaurant in itself is puzzling.

Doikanoi ໂດຽຂ້ານ້ອຽ dòːy kʰȁː nɔ̑ːy is a term used in the Lao hierarchical society before 1975 that conveys that you are inferior or younger than the person you are talking to. It is equivalent to “yes, Sir / yes, Madam, I am at your service”. Noi was a rural child born after the Revolution, therefore not influenced by the structure of a royalist society overthrown by the communist regime. I wonder what made her choose that name. I would like to think that it is her modesty and respect for others. Insta photos of Noi appear here and there, at the market, cooking, cleaning a fish or on a motorbike carrying fresh finds from the market. She is a ສຸພາບສັຕຣີ súpʰâːp sá triː “a gentlewoman” exemplifying the qualities of courtesy, good manners, and gentleness of Lao women.

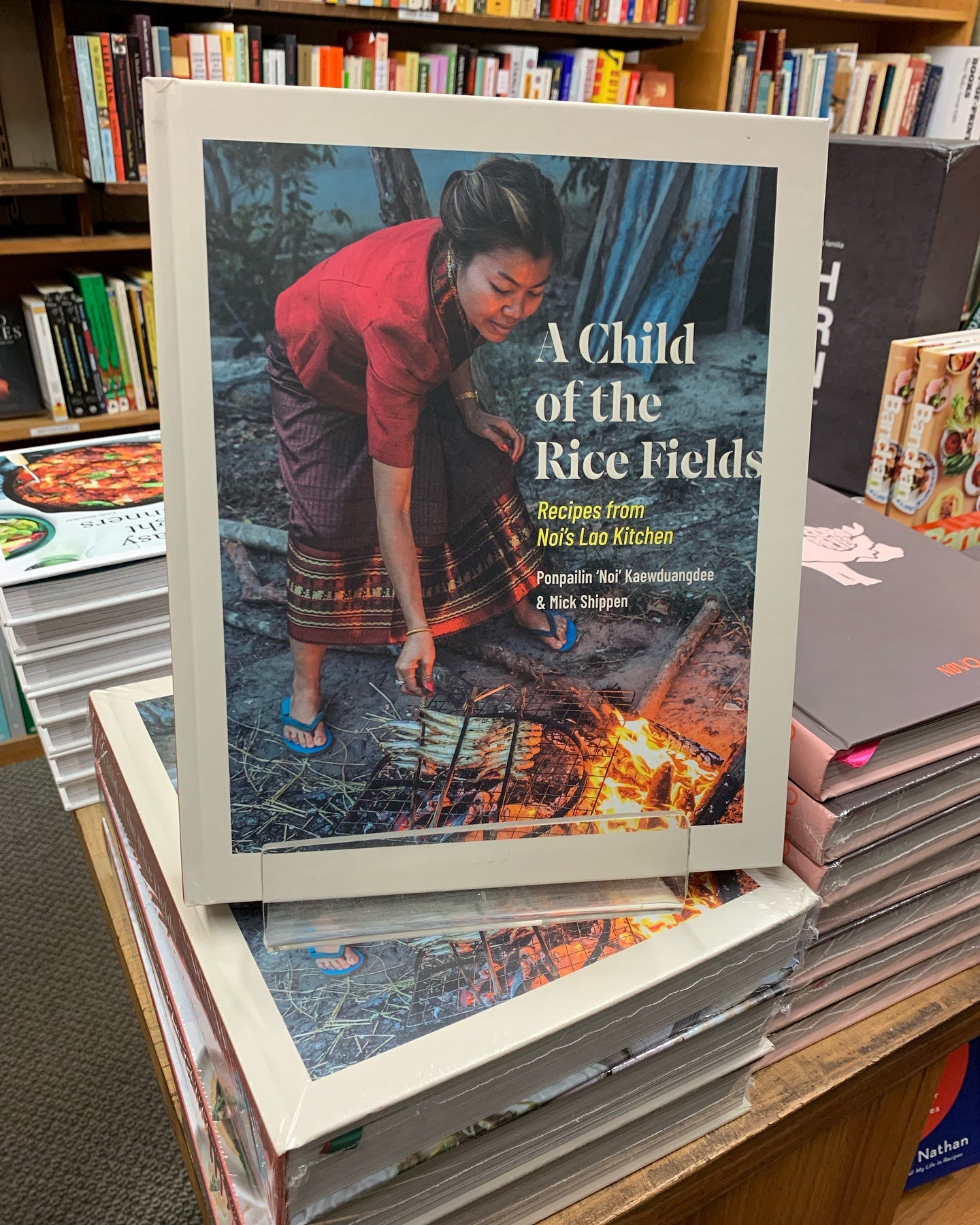

When her cookbook came out4, it took me a while to understand that the recipes were Noi’s voice. The text and photos were Mick’s labor of love to capture Noi’s cuisine, an outside-in view of Lao food, foundational for younger generations of Lao living overseas and many others eager to learn about Lao food. I messaged Mick on Insta: “Someone carried the book for me. Congratulations for that too! I have comments of course, maybe one day when we meet face to face around a good meal”. Sadly, this meal will not be one prepared by Noi. Whatever comments I might have in those early days sound now foolish.

This cookbook is Noi’s legacy. Mick documented with great attention how she cooked, the sequencing, the how-to, the tour-de-main. He explains the ABC of Lao food, gives tips that only Lao people know, how to keep the glutinous rice in a plastic bag and reheat it swiftly with the microwave. The book allows now to recreate with precision Noi’s recipes.

I look at the photos on the Insta feed as I write this eulogy. I feel so much sadness, for those gifted who leave us too soon, when they have the world in their hands and can change the way we see things. In fact, she does, as we continue to honor her food. May you rest in Peace, Noi, and may you find strength, Mick, family and friends.

Notably about the transliteration of Lao words into English as I suggested to use the phonetic system established by linguists.

ພຶ້ນເມືອງ pʰɨ̑ːn mɨ́aːŋ : indigenous, native; provincial, local, domestic.

ພຶ້ນບ້ານ pʰɨ̑ːn bȃːn : area of home, house; village.

A few articles can be found here: https://champameuanglao.com/the-tastes-of-laos/

https://theaseanmagazine.asean.org/article/preserving-traditional-lao-flavours/

https://laotiantimes.com/2024/09/17/a-child-of-the-rice-fields-recipes-from-nois-lao-kitchen/

https://phakhaolao.la/en/champion/noi-owner-and-culinary-artist-at-doi-ka-noi/

Shippen M., Kaewduangdee P. (2024). A Child of the Rice Fields, Recipes from Noi’s Lao Kitchen. Self published. The book can be found in Laos or at Kitchen Arts and Letters in NYC https://g.co/kgs/GXi6PkS